Not to be confused with geranium.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Germanium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | (jur-MAY-nee-əm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | grayish-white | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Ge) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

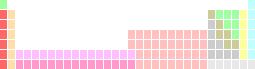

| Germanium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

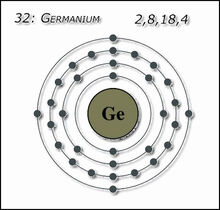

| Atomic number (Z) | 32 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 14 (carbon group) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

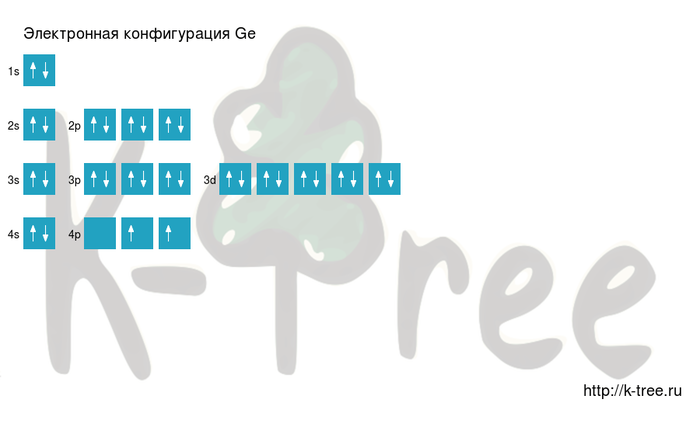

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d10 4s2 4p2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

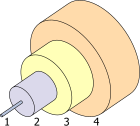

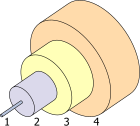

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1211.40 K (938.25 °C, 1720.85 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 3106 K (2833 °C, 5131 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 5.323 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 5.60 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 36.94 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 334 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 23.222 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −4 −3, −2, −1, 0,[2] +1, +2, +3, +4 (an amphoteric oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.01 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 122 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 122 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 211 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of germanium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centered diamond-cubic

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 5400 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 6.0 µm/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 60.2 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 1 Ω⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Band gap | 0.67 eV (at 300 K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | −76.84×10−6 cm3/mol[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 103 GPa[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 41 GPa[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 75 GPa[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.26[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 6.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-56-4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after Germany, homeland of the discoverer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prediction | Dmitri Mendeleev (1869) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Clemens Winkler (1886) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main isotopes of germanium

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Germanium is a chemical element with the symbol Ge and atomic number 32. It is lustrous, hard-brittle, grayish-white and similar in appearance to silicon. It is a metalloid in the carbon group that is chemically similar to its group neighbors silicon and tin. Like silicon, germanium naturally reacts and forms complexes with oxygen in nature.

Because it seldom appears in high concentration, germanium was discovered comparatively late in the discovery of the elements. Germanium ranks near fiftieth in relative abundance of the elements in the Earth’s crust. In 1869, Dmitri Mendeleev predicted its existence and some of its properties from its position on his periodic table, and called the element ekasilicon. In 1886, Clemens Winkler at Freiberg University found the new element, along with silver and sulfur, in the mineral argyrodite. Winkler named the element after his country, Germany. Germanium is mined primarily from sphalerite (the primary ore of zinc), though germanium is also recovered commercially from silver, lead, and copper ores.

Elemental germanium is used as a semiconductor in transistors and various other electronic devices. Historically, the first decade of semiconductor electronics was based entirely on germanium. Presently, the major end uses are fibre-optic systems, infrared optics, solar cell applications, and light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Germanium compounds are also used for polymerization catalysts and have most recently found use in the production of nanowires. This element forms a large number of organogermanium compounds, such as tetraethylgermanium, useful in organometallic chemistry. Germanium is considered a technology-critical element.[6]

Germanium is not thought to be an essential element for any living organism. Similar to silicon and aluminium, naturally-occurring germanium compounds tend to be insoluble in water and thus have little oral toxicity. However, synthetic soluble germanium salts are nephrotoxic, and synthetic chemically reactive germanium compounds with halogens and hydrogen are irritants and toxins.

History[edit]

Prediction of germanium, «?=70» (periodic table 1869)

In his report on The Periodic Law of the Chemical Elements in 1869, the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev predicted the existence of several unknown chemical elements, including one that would fill a gap in the carbon family, located between silicon and tin.[7] Because of its position in his periodic table, Mendeleev called it ekasilicon (Es), and he estimated its atomic weight to be 70 (later 72).

In mid-1885, at a mine near Freiberg, Saxony, a new mineral was discovered and named argyrodite because of its high silver content.[note 1] The chemist Clemens Winkler analyzed this new mineral, which proved to be a combination of silver, sulfur, and a new element. Winkler was able to isolate the new element in 1886 and found it similar to antimony. He initially considered the new element to be eka-antimony, but was soon convinced that it was instead eka-silicon.[9][10] Before Winkler published his results on the new element, he decided that he would name his element neptunium, since the recent discovery of planet Neptune in 1846 had similarly been preceded by mathematical predictions of its existence.[note 2] However, the name «neptunium» had already been given to another proposed chemical element (though not the element that today bears the name neptunium, which was discovered in 1940).[note 3] So instead, Winkler named the new element germanium (from the Latin word, Germania, for Germany) in honor of his homeland.[10] Argyrodite proved empirically to be Ag8GeS6.

Because this new element showed some similarities with the elements arsenic and antimony, its proper place in the periodic table was under consideration, but its similarities with Dmitri Mendeleev’s predicted element «ekasilicon» confirmed that place on the periodic table.[10][17] With further material from 500 kg of ore from the mines in Saxony, Winkler confirmed the chemical properties of the new element in 1887.[9][10][18] He also determined an atomic weight of 72.32 by analyzing pure germanium tetrachloride (GeCl

4), while Lecoq de Boisbaudran deduced 72.3 by a comparison of the lines in the spark spectrum of the element.[19]

Winkler was able to prepare several new compounds of germanium, including fluorides, chlorides, sulfides, dioxide, and tetraethylgermane (Ge(C2H5)4), the first organogermane.[9] The physical data from those compounds—which corresponded well with Mendeleev’s predictions—made the discovery an important confirmation of Mendeleev’s idea of element periodicity. Here is a comparison between the prediction and Winkler’s data:[9]

| Property | Ekasilicon Mendeleev prediction (1871) | Germanium Winkler discovery (1887) |

|---|---|---|

| atomic mass | 72.64 | 72.63 |

| density (g/cm3) | 5.5 | 5.35 |

| melting point (°C) | high | 947 |

| color | gray | gray |

| oxide type | refractory dioxide | refractory dioxide |

| oxide density (g/cm3) | 4.7 | 4.7 |

| oxide activity | feebly basic | feebly basic |

| chloride boiling point (°C) | under 100 | 86 (GeCl4) |

| chloride density (g/cm3) | 1.9 | 1.9 |

Until the late 1930s, germanium was thought to be a poorly conducting metal.[20] Germanium did not become economically significant until after 1945 when its properties as an electronic semiconductor were recognized. During World War II, small amounts of germanium were used in some special electronic devices, mostly diodes.[21][22] The first major use was the point-contact Schottky diodes for radar pulse detection during the War.[20] The first silicon-germanium alloys were obtained in 1955.[23] Before 1945, only a few hundred kilograms of germanium were produced in smelters each year, but by the end of the 1950s, the annual worldwide production had reached 40 metric tons (44 short tons).[24]

The development of the germanium transistor in 1948[25] opened the door to countless applications of solid state electronics.[26] From 1950 through the early 1970s, this area provided an increasing market for germanium, but then high-purity silicon began replacing germanium in transistors, diodes, and rectifiers.[27] For example, the company that became Fairchild Semiconductor was founded in 1957 with the express purpose of producing silicon transistors. Silicon has superior electrical properties, but it requires much greater purity that could not be commercially achieved in the early years of semiconductor electronics.[28]

Meanwhile, the demand for germanium for fiber optic communication networks, infrared night vision systems, and polymerization catalysts increased dramatically.[24] These end uses represented 85% of worldwide germanium consumption in 2000.[27] The US government even designated germanium as a strategic and critical material, calling for a 146 ton (132 tonne) supply in the national defense stockpile in 1987.[24]

Germanium differs from silicon in that the supply is limited by the availability of exploitable sources, while the supply of silicon is limited only by production capacity since silicon comes from ordinary sand and quartz. While silicon could be bought in 1998 for less than $10 per kg,[24] the price of germanium was almost $800 per kg.[24]

Characteristics[edit]

Under standard conditions, germanium is a brittle, silvery-white, semi-metallic element.[29] This form constitutes an allotrope known as α-germanium, which has a metallic luster and a diamond cubic crystal structure, the same as diamond.[27] While in crystal form, germanium has a displacement threshold energy of

Germanium is a semiconductor having an indirect bandgap, as is crystalline silicon. Zone refining techniques have led to the production of crystalline germanium for semiconductors that has an impurity of only one part in 1010,[32]

making it one of the purest materials ever obtained.[33]

The first metallic material discovered (in 2005) to become a superconductor in the presence of an extremely strong electromagnetic field was an alloy of germanium, uranium, and rhodium.[34]

Pure germanium is known to spontaneously extrude very long screw dislocations, referred to as germanium whiskers. The growth of these whiskers is one of the primary reasons for the failure of older diodes and transistors made from germanium, as, depending on what they eventually touch, they may lead to an electrical short.[35]

Chemistry[edit]

Elemental germanium starts to oxidize slowly in air at around 250 °C, forming GeO2 .[36] Germanium is insoluble in dilute acids and alkalis but dissolves slowly in hot concentrated sulfuric and nitric acids and reacts violently with molten alkalis to produce germanates ([GeO

3]2−

). Germanium occurs mostly in the oxidation state +4 although many +2 compounds are known.[37] Other oxidation states are rare: +3 is found in compounds such as Ge2Cl6, and +3 and +1 are found on the surface of oxides,[38] or negative oxidation states in germanides, such as −4 in Mg

2Ge. Germanium cluster anions (Zintl ions) such as Ge42−, Ge94−, Ge92−, [(Ge9)2]6− have been prepared by the extraction from alloys containing alkali metals and germanium in liquid ammonia in the presence of ethylenediamine or a cryptand.[37][39] The oxidation states of the element in these ions are not integers—similar to the ozonides O3−.

Two oxides of germanium are known: germanium dioxide (GeO

2, germania) and germanium monoxide, (GeO).[31] The dioxide, GeO2 can be obtained by roasting germanium disulfide (GeS

2), and is a white powder that is only slightly soluble in water but reacts with alkalis to form germanates.[31] The monoxide, germanous oxide, can be obtained by the high temperature reaction of GeO2 with Ge metal.[31] The dioxide (and the related oxides and germanates) exhibits the unusual property of having a high refractive index for visible light, but transparency to infrared light.[40][41] Bismuth germanate, Bi4Ge3O12, (BGO) is used as a scintillator.[42]

Binary compounds with other chalcogens are also known, such as the disulfide (GeS

2), diselenide (GeSe

2), and the monosulfide (GeS), selenide (GeSe), and telluride (GeTe).[37] GeS2 forms as a white precipitate when hydrogen sulfide is passed through strongly acid solutions containing Ge(IV).[37] The disulfide is appreciably soluble in water and in solutions of caustic alkalis or alkaline sulfides. Nevertheless, it is not soluble in acidic water, which allowed Winkler to discover the element.[43] By heating the disulfide in a current of hydrogen, the monosulfide (GeS) is formed, which sublimes in thin plates of a dark color and metallic luster, and is soluble in solutions of the caustic alkalis.[31] Upon melting with alkaline carbonates and sulfur, germanium compounds form salts known as thiogermanates.[44]

Four tetrahalides are known. Under normal conditions GeI4 is a solid, GeF4 a gas and the others volatile liquids. For example, germanium tetrachloride, GeCl4, is obtained as a colorless fuming liquid boiling at 83.1 °C by heating the metal with chlorine.[31] All the tetrahalides are readily hydrolyzed to hydrated germanium dioxide.[31] GeCl4 is used in the production of organogermanium compounds.[37] All four dihalides are known and in contrast to the tetrahalides are polymeric solids.[37] Additionally Ge2Cl6 and some higher compounds of formula GenCl2n+2 are known.[31] The unusual compound Ge6Cl16 has been prepared that contains the Ge5Cl12 unit with a neopentane structure.[45]

Germane (GeH4) is a compound similar in structure to methane. Polygermanes—compounds that are similar to alkanes—with formula GenH2n+2 containing up to five germanium atoms are known.[37] The germanes are less volatile and less reactive than their corresponding silicon analogues.[37] GeH4 reacts with alkali metals in liquid ammonia to form white crystalline MGeH3 which contain the GeH3− anion.[37] The germanium hydrohalides with one, two and three halogen atoms are colorless reactive liquids.[37]

The first organogermanium compound was synthesized by Winkler in 1887; the reaction of germanium tetrachloride with diethylzinc yielded tetraethylgermane (Ge(C

2H

5)

4).[9] Organogermanes of the type R4Ge (where R is an alkyl) such as tetramethylgermane (Ge(CH

3)

4) and tetraethylgermane are accessed through the cheapest available germanium precursor germanium tetrachloride and alkyl nucleophiles. Organic germanium hydrides such as isobutylgermane ((CH

3)

2CHCH

2GeH

3) were found to be less hazardous and may be used as a liquid substitute for toxic germane gas in semiconductor applications. Many germanium reactive intermediates are known: germyl free radicals, germylenes (similar to carbenes), and germynes (similar to carbynes).[46][47] The organogermanium compound 2-carboxyethylgermasesquioxane was first reported in the 1970s, and for a while was used as a dietary supplement and thought to possibly have anti-tumor qualities.[48]

Using a ligand called Eind (1,1,3,3,5,5,7,7-octaethyl-s-hydrindacen-4-yl) germanium is able to form a double bond with oxygen (germanone). Germanium hydride and germanium tetrahydride are very flammable and even explosive when mixed with air.[49]

Isotopes[edit]

Germanium occurs in 5 natural isotopes: 70

Ge

, 72

Ge

, 73

Ge

, 74

Ge

, and 76

Ge

. Of these, 76

Ge

is very slightly radioactive, decaying by double beta decay with a half-life of 1.78×1021 years. 74

Ge

is the most common isotope, having a natural abundance of approximately 36%. 76

Ge

is the least common with a natural abundance of approximately 7%.[50] When bombarded with alpha particles, the isotope 72

Ge

will generate stable 77

Se

, releasing high energy electrons in the process.[51] Because of this, it is used in combination with radon for nuclear batteries.[51]

At least 27 radioisotopes have also been synthesized, ranging in atomic mass from 58 to 89. The most stable of these is 68

Ge

, decaying by electron capture with a half-life of 270.95 days. The least stable is 60

Ge

, with a half-life of 30 ms. While most of germanium’s radioisotopes decay by beta decay, 61

Ge

and 64

Ge

decay by

β+

delayed proton emission.[50] 84

Ge

through 87

Ge

isotopes also exhibit minor

β−

delayed neutron emission decay paths.[50]

Occurrence[edit]

Germanium is created by stellar nucleosynthesis, mostly by the s-process in asymptotic giant branch stars. The s-process is a slow neutron capture of lighter elements inside pulsating red giant stars.[52] Germanium has been detected in some of the most distant stars[53] and in the atmosphere of Jupiter.[54]

Germanium’s abundance in the Earth’s crust is approximately 1.6 ppm.[55] Only a few minerals like argyrodite, briartite, germanite, renierite and sphalerite contain appreciable amounts of germanium.[27][56] Only few of them (especially germanite) are, very rarely, found in mineable amounts.[57][58][59] Some zinc-copper-lead ore bodies contain enough germanium to justify extraction from the final ore concentrate.[55] An unusual natural enrichment process causes a high content of germanium in some coal seams, discovered by Victor Moritz Goldschmidt during a broad survey for germanium deposits.[60][61] The highest concentration ever found was in Hartley coal ash with as much as 1.6% germanium.[60][61] The coal deposits near Xilinhaote, Inner Mongolia, contain an estimated 1600 tonnes of germanium.[55]

Production[edit]

About 118 tonnes of germanium were produced in 2011 worldwide, mostly in China (80 t), Russia (5 t) and United States (3 t).[27] Germanium is recovered as a by-product from sphalerite zinc ores where it is concentrated in amounts as great as 0.3%,[62] especially from low-temperature sediment-hosted, massive Zn–Pb–Cu(–Ba) deposits and carbonate-hosted Zn–Pb deposits.[63] A recent study found that at least 10,000 t of extractable germanium is contained in known zinc reserves, particularly those hosted by Mississippi-Valley type deposits, while at least 112,000 t will be found in coal reserves.[64][65] In 2007 35% of the demand was met by recycled germanium.[55]

| Year | Cost ($/kg)[66] |

|---|---|

| 1999 | 1,400 |

| 2000 | 1,250 |

| 2001 | 890 |

| 2002 | 620 |

| 2003 | 380 |

| 2004 | 600 |

| 2005 | 660 |

| 2006 | 880 |

| 2007 | 1,240 |

| 2008 | 1,490 |

| 2009 | 950 |

| 2010 | 940 |

| 2011 | 1,625 |

| 2012 | 1,680 |

| 2013 | 1,875 |

| 2014 | 1,900 |

| 2015 | 1,760 |

| 2016 | 950 |

| 2017 | 1,358 |

| 2018 | 1,300 |

| 2019 | 1,240 |

| 2020 | 1,000 |

While it is produced mainly from sphalerite, it is also found in silver, lead, and copper ores. Another source of germanium is fly ash of power plants fueled from coal deposits that contain germanium. Russia and China used this as a source for germanium.[67] Russia’s deposits are located in the far east of Sakhalin Island, and northeast of Vladivostok. The deposits in China are located mainly in the lignite mines near Lincang, Yunnan; coal is also mined near Xilinhaote, Inner Mongolia.[55]

The ore concentrates are mostly sulfidic; they are converted to the oxides by heating under air in a process known as roasting:

- GeS2 + 3 O2 → GeO2 + 2 SO2

Some of the germanium is left in the dust produced, while the rest is converted to germanates, which are then leached (together with zinc) from the cinder by sulfuric acid. After neutralization, only the zinc stays in solution while germanium and other metals precipitate. After removing some of the zinc in the precipitate by the Waelz process, the residing Waelz oxide is leached a second time. The dioxide is obtained as precipitate and converted with chlorine gas or hydrochloric acid to germanium tetrachloride, which has a low boiling point and can be isolated by distillation:[67]

- GeO2 + 4 HCl → GeCl4 + 2 H2O

- GeO2 + 2 Cl2 → GeCl4 + O2

Germanium tetrachloride is either hydrolyzed to the oxide (GeO2) or purified by fractional distillation and then hydrolyzed.[67] The highly pure GeO2 is now suitable for the production of germanium glass. It is reduced to the element by reacting it with hydrogen, producing germanium suitable for infrared optics and semiconductor production:

- GeO2 + 2 H2 → Ge + 2 H2O

The germanium for steel production and other industrial processes is normally reduced using carbon:[68]

- GeO2 + C → Ge + CO2

Applications[edit]

The major end uses for germanium in 2007, worldwide, were estimated to be: 35% for fiber-optics, 30% infrared optics, 15% polymerization catalysts, and 15% electronics and solar electric applications.[27] The remaining 5% went into such uses as phosphors, metallurgy, and chemotherapy.[27]

Optics[edit]

A typical single-mode optical fiber. Germanium oxide is a dopant of the core silica (Item 1).

- Core 8 µm

- Cladding 125 µm

- Buffer 250 µm

- Jacket 400 µm

The notable properties of germania (GeO2) are its high index of refraction and its low optical dispersion. These make it especially useful for wide-angle camera lenses, microscopy, and the core part of optical fibers.[69][70] It has replaced titania as the dopant for silica fiber, eliminating the subsequent heat treatment that made the fibers brittle.[71] At the end of 2002, the fiber optics industry consumed 60% of the annual germanium use in the United States, but this is less than 10% of worldwide consumption.[70] GeSbTe is a phase change material used for its optic properties, such as that used in rewritable DVDs.[72]

Because germanium is transparent in the infrared wavelengths, it is an important infrared optical material that can be readily cut and polished into lenses and windows. It is especially used as the front optic in thermal imaging cameras working in the 8 to 14 micron range for passive thermal imaging and for hot-spot detection in military, mobile night vision, and fire fighting applications.[68] It is used in infrared spectroscopes and other optical equipment that require extremely sensitive infrared detectors.[70] It has a very high refractive index (4.0) and must be coated with anti-reflection agents. Particularly, a very hard special antireflection coating of diamond-like carbon (DLC), refractive index 2.0, is a good match and produces a diamond-hard surface that can withstand much environmental abuse.[73][74]

Electronics[edit]

Germanium can be alloyed with silicon, and silicon-germanium alloys are rapidly becoming an important semiconductor material for high-speed integrated circuits. Circuits utilizing the properties of Si-SiGe heterojunctions can be much faster than those using silicon alone.[75] Silicon-germanium is beginning to replace gallium arsenide (GaAs) in wireless communications devices.[27] The SiGe chips, with high-speed properties, can be made with low-cost, well-established production techniques of the silicon chip industry.[27]

High efficiency solar panels are a major use of germanium. Because germanium and gallium arsenide have nearly identical lattice constant, germanium substrates can be used to make gallium-arsenide solar cells.[76] Germanium is the substrate of the wafers for high-efficiency multijunction photovoltaic cells for space applications, such as the Mars Exploration Rovers, which use triple-junction gallium arsenide on germanium cells.[77] High-brightness LEDs, used for automobile headlights and to backlight LCD screens, are also an important application.[27]

Germanium-on-insulator (GeOI) substrates are seen as a potential replacement for silicon on miniaturized chips.[27] CMOS circuit based on GeOI substrates has been reported recently.[78] Other uses in electronics include phosphors in fluorescent lamps[32] and solid-state light-emitting diodes (LEDs).[27] Germanium transistors are still used in some effects pedals by musicians who wish to reproduce the distinctive tonal character of the «fuzz»-tone from the early rock and roll era, most notably the Dallas Arbiter Fuzz Face.[79]

Other uses[edit]

Germanium dioxide is also used in catalysts for polymerization in the production of polyethylene terephthalate (PET).[80] The high brilliance of this polyester is especially favored for PET bottles marketed in Japan.[80] In the United States, germanium is not used for polymerization catalysts.[27]

Due to the similarity between silica (SiO2) and germanium dioxide (GeO2), the silica stationary phase in some gas chromatography columns can be replaced by GeO2.[81]

In recent years germanium has seen increasing use in precious metal alloys. In sterling silver alloys, for instance, it reduces firescale, increases tarnish resistance, and improves precipitation hardening. A tarnish-proof silver alloy trademarked Argentium contains 1.2% germanium.[27]

Semiconductor detectors made of single crystal high-purity germanium can precisely identify radiation sources—for example in airport security.[82] Germanium is useful for monochromators for beamlines used in single crystal neutron scattering and synchrotron X-ray diffraction. The reflectivity has advantages over silicon in neutron and high energy X-ray applications.[83] Crystals of high purity germanium are used in detectors for gamma spectroscopy and the search for dark matter.[84] Germanium crystals are also used in X-ray spectrometers for the determination of phosphorus, chlorine and sulfur.[85]

Germanium is emerging as an important material for spintronics and spin-based quantum computing applications. In 2010, researchers demonstrated room temperature spin transport[86] and more recently donor electron spins in germanium has been shown to have very long coherence times.[87]

Germanium and health[edit]

Germanium is not considered essential to the health of plants or animals.[88] Germanium in the environment has little or no health impact. This is primarily because it usually occurs only as a trace element in ores and carbonaceous materials, and the various industrial and electronic applications involve very small quantities that are not likely to be ingested.[27] For similar reasons, end-use germanium has little impact on the environment as a biohazard. Some reactive intermediate compounds of germanium are poisonous (see precautions, below).[89]

Germanium supplements, made from both organic and inorganic germanium, have been marketed as an alternative medicine capable of treating leukemia and lung cancer.[24] There is, however, no medical evidence of benefit; some evidence suggests that such supplements are actively harmful.[88] U.S. Food and Drug Administration research has concluded that inorganic germanium, when used as a nutritional supplement, «presents potential human health hazard».[48]

Some germanium compounds have been administered by alternative medical practitioners as non-FDA-allowed injectable solutions. Soluble inorganic forms of germanium used at first, notably the citrate-lactate salt, resulted in some cases of renal dysfunction, hepatic steatosis, and peripheral neuropathy in individuals using them over a long term. Plasma and urine germanium concentrations in these individuals, several of whom died, were several orders of magnitude greater than endogenous levels. A more recent organic form, beta-carboxyethylgermanium sesquioxide (propagermanium), has not exhibited the same spectrum of toxic effects.[90]

Certain compounds of germanium have low toxicity to mammals, but have toxic effects against certain bacteria.[29]

Precautions for chemically reactive germanium compounds[edit]

While use of germanium itself does not require precautions, some of germanium’s artificially produced compounds are quite reactive and present an immediate hazard to human health on exposure. For example, germanium chloride and germane (GeH4) are a liquid and gas, respectively, that can be very irritating to the eyes, skin, lungs, and throat.[91]

See also[edit]

- Germanene

- Vitrain

- History of the transistor

Notes[edit]

- ^ From Greek, argyrodite means silver-containing.[8]

- ^ Just as the existence of the new element had been predicted, the existence of the planet Neptune had been predicted in about 1843 by the two mathematicians John Couch Adams and Urbain Le Verrier, using the calculation methods of celestial mechanics. They did this in attempts to explain the fact that the planet Uranus, upon very close observation, appeared to be being pulled slightly out of position in the sky.[11] James Challis started searching for it in July 1846, and he sighted this planet on September 23, 1846.[12]

- ^ R. Hermann published claims in 1877 of his discovery of a new element beneath tantalum in the periodic table, which he named neptunium, after the Greek god of the oceans and seas.[13][14] However this metal was later recognized to be an alloy of the elements niobium and tantalum.[15] The name «neptunium» was later given to the synthetic element one step past uranium in the Periodic Table, which was discovered by nuclear physics researchers in 1940.[16]

References[edit]

- ^ «Standard Atomic Weights: Germanium». CIAAW. 2009.

- ^ «New Type of Zero-Valent Tin Compound». Chemistry Europe. 27 August 2016.

- ^ Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds, in Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 81st edition, CRC press.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ a b c d «Properties of Germanium». Ioffe Institute.

- ^ Avarmaa, Katri; Klemettinen, Lassi; O’Brien, Hugh; Taskinen, Pekka; Jokilaakso, Ari (June 2019). «Critical Metals Ga, Ge and In: Experimental Evidence for Smelter Recovery Improvements». Minerals. 9 (6): 367. Bibcode:2019Mine….9..367A. doi:10.3390/min9060367.

- ^ Kaji, Masanori (2002). «D. I. Mendeleev’s concept of chemical elements and The Principles of Chemistry» (PDF). Bulletin for the History of Chemistry. 27 (1): 4–16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-17. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ^ Argyrodite – Ag

8GeS

6 (PDF) (Report). Mineral Data Publishing. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2008-09-01. - ^ a b c d e Winkler, Clemens (1887). «Mittheilungen über des Germanium. Zweite Abhandlung». J. Prak. Chemie (in German). 36 (1): 177–209. doi:10.1002/prac.18870360119. Archived from the original on 2012-11-03. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ^ a b c d Winkler, Clemens (1887). «Germanium, Ge, a New Nonmetal Element». Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 19 (1): 210–211. doi:10.1002/cber.18860190156. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008.

- ^ Adams, J. C. (November 13, 1846). «Explanation of the observed irregularities in the motion of Uranus, on the hypothesis of disturbance by a more distant planet». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 7 (9): 149–152. Bibcode:1846MNRAS…7..149A. doi:10.1093/mnras/7.9.149. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved August 25, 2019.

- ^ Challis, Rev. J. (November 13, 1846). «Account of observations at the Cambridge observatory for detecting the planet exterior to Uranus». Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 7 (9): 145–149. Bibcode:1846MNRAS…7..145C. doi:10.1093/mnras/7.9.145. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 4, 2019. Retrieved August 25, 2019.

- ^ Sears, Robert (July 1877). Scientific Miscellany. The Galaxy. Vol. 24. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-665-50166-1. OCLC 16890343.

- ^ «Editor’s Scientific Record». Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. 55 (325): 152–153. June 1877. Archived from the original on 2012-05-26. Retrieved 2008-09-22.

- ^ van der Krogt, Peter. «Elementymology & Elements Multidict: Niobium». Archived from the original on 2010-01-23. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ^ Westgren, A. (1964). «The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1951: presentation speech». Nobel Lectures, Chemistry 1942–1962. Elsevier. Archived from the original on 2008-12-10. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ^ «Germanium, a New Non-Metallic Element». The Manufacturer and Builder: 181. 1887. Archived from the original on 2008-12-19. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ^ Brunck, O. (1886). «Obituary: Clemens Winkler». Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 39 (4): 4491–4548. doi:10.1002/cber.190603904164. Archived from the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- ^ de Boisbaudran, M. Lecoq (1886). «Sur le poids atomique du germanium». Comptes Rendus (in French). 103: 452. Archived from the original on 2013-06-20. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ^ a b Haller, E. E. (2006-06-14). «Germanium: From Its Discovery to SiGe Devices» (PDF). Department of Materials Science and Engineering, University of California, Berkeley, and Materials Sciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-07-10. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ W. K. (1953-05-10). «Germanium for Electronic Devices». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2013-06-13. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ «1941 – Semiconductor diode rectifiers serve in WW II». Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on 2008-09-24. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ «SiGe History». University of Cambridge. Archived from the original on 2008-08-05. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ a b c d e f Halford, Bethany (2003). «Germanium». Chemical & Engineering News. American Chemical Society. Archived from the original on 2008-05-13. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ Bardeen, J.; Brattain, W. H. (1948). «The Transistor, A Semi-Conductor Triode». Physical Review. 74 (2): 230–231. Bibcode:1948PhRv…74..230B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.74.230.

- ^ «Electronics History 4 – Transistors». National Academy of Engineering. Archived from the original on 2007-10-20. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o U.S. Geological Survey (2008). «Germanium – Statistics and Information». U.S. Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries. Archived from the original on 2008-09-16. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

Select 2008

- ^ Teal, Gordon K. (July 1976). «Single Crystals of Germanium and Silicon-Basic to the Transistor and Integrated Circuit». IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices. ED-23 (7): 621–639. Bibcode:1976ITED…23..621T. doi:10.1109/T-ED.1976.18464. S2CID 11910543.

- ^ a b Emsley, John (2001). Nature’s Building Blocks. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 506–510. ISBN 978-0-19-850341-5.

- ^ Agnese, R.; Aralis, T.; Aramaki, T.; Arnquist, I. J.; Azadbakht, E.; Baker, W.; Banik, S.; Barker, D.; Bauer, D. A. (2018-08-27). «Energy loss due to defect formation from 206Pb recoils in SuperCDMS germanium detectors». Applied Physics Letters. 113 (9): 092101. arXiv:1805.09942. Bibcode:2018ApPhL.113i2101A. doi:10.1063/1.5041457. ISSN 0003-6951. S2CID 118627298.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E.; Wiberg, N. (2007). Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (102nd ed.). de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-017770-1. OCLC 145623740.

- ^ a b «Germanium». Los Alamos National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 2011-06-22. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

- ^

Chardin, B. (2001). «Dark Matter: Direct Detection». In Binetruy, B (ed.). The Primordial Universe: 28 June – 23 July 1999. Springer. p. 308. ISBN 978-3-540-41046-1. - ^

Lévy, F.; Sheikin, I.; Grenier, B.; Huxley, A. (August 2005). «Magnetic field-induced superconductivity in the ferromagnet URhGe». Science. 309 (5739): 1343–1346. Bibcode:2005Sci…309.1343L. doi:10.1126/science.1115498. PMID 16123293. S2CID 38460998. - ^ Givargizov, E. I. (1972). «Morphology of Germanium Whiskers». Kristall und Technik. 7 (1–3): 37–41. doi:10.1002/crat.19720070107.

- ^ Tabet, N; Salim, Mushtaq A. (1998). «KRXPS study of the oxidation of Ge(001) surface». Applied Surface Science. 134 (1–4): 275–282. Bibcode:1998ApSS..134..275T. doi:10.1016/S0169-4332(98)00251-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Tabet, N; Salim, M. A.; Al-Oteibi, A. L. (1999). «XPS study of the growth kinetics of thin films obtained by thermal oxidation of germanium substrates». Journal of Electron Spectroscopy and Related Phenomena. 101–103: 233–238. doi:10.1016/S0368-2048(98)00451-4.

- ^ Xu, Li; Sevov, Slavi C. (1999). «Oxidative Coupling of Deltahedral [Ge9]4− Zintl Ions». J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 (39): 9245–9246. doi:10.1021/ja992269s.

- ^ Bayya, Shyam S.; Sanghera, Jasbinder S.; Aggarwal, Ishwar D.; Wojcik, Joshua A. (2002). «Infrared Transparent Germanate Glass-Ceramics». Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 85 (12): 3114–3116. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.2002.tb00594.x.

- ^ Drugoveiko, O. P.; Evstrop’ev, K. K.; Kondrat’eva, B. S.; Petrov, Yu. A.; Shevyakov, A. M. (1975). «Infrared reflectance and transmission spectra of germanium dioxide and its hydrolysis products». Journal of Applied Spectroscopy. 22 (2): 191–193. Bibcode:1975JApSp..22..191D. doi:10.1007/BF00614256. S2CID 97581394.

- ^ Lightstone, A. W.; McIntyre, R. J.; Lecomte, R.; Schmitt, D. (1986). «A Bismuth Germanate-Avalanche Photodiode Module Designed for Use in High Resolution Positron Emission Tomography». IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science. 33 (1): 456–459. Bibcode:1986ITNS…33..456L. doi:10.1109/TNS.1986.4337142. S2CID 682173.

- ^ Johnson, Otto H. (1952). «Germanium and its Inorganic Compounds». Chem. Rev. 51 (3): 431–469. doi:10.1021/cr60160a002.

- ^ Fröba, Michael; Oberender, Nadine (1997). «First synthesis of mesostructured thiogermanates». Chemical Communications (18): 1729–1730. doi:10.1039/a703634e.

- ^ Beattie, I.R.; Jones, P.J.; Reid, G.; Webster, M. (1998). «The Crystal Structure and Raman Spectrum of Ge5Cl12·GeCl4 and the Vibrational Spectrum of Ge2Cl6«. Inorg. Chem. 37 (23): 6032–6034. doi:10.1021/ic9807341. PMID 11670739.

- ^ Satge, Jacques (1984). «Reactive intermediates in organogermanium chemistry». Pure Appl. Chem. 56 (1): 137–150. doi:10.1351/pac198456010137. S2CID 96576323.

- ^ Quane, Denis; Bottei, Rudolph S. (1963). «Organogermanium Chemistry». Chemical Reviews. 63 (4): 403–442. doi:10.1021/cr60224a004.

- ^ a b Tao, S. H.; Bolger, P. M. (June 1997). «Hazard Assessment of Germanium Supplements». Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 25 (3): 211–219. doi:10.1006/rtph.1997.1098. PMID 9237323. Archived from the original on 2020-03-10. Retrieved 2019-06-30.

- ^ Broadwith, Phillip (25 March 2012). «Germanium-oxygen double bond takes centre stage». Chemistry World. Archived from the original on 2014-05-17. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ a b c Audi, Georges; Bersillon, Olivier; Blachot, Jean; Wapstra, Aaldert Hendrik (2003), «The NUBASE evaluation of nuclear and decay properties», Nuclear Physics A, 729: 3–128, Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729….3A, doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001

- ^ a b Perreault, Bruce A. «Alpha Fusion Electrical Energy Valve», US Patent 7800286, issued September 21, 2010. PDF copy at the Wayback Machine (archived October 12, 2007)

- ^ Sterling, N. C.; Dinerstein, Harriet L.; Bowers, Charles W. (2002). «Discovery of Enhanced Germanium Abundances in Planetary Nebulae with the Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer». The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 578 (1): L55–L58. arXiv:astro-ph/0208516. Bibcode:2002ApJ…578L..55S. doi:10.1086/344473. S2CID 119395123.

- ^ Cowan, John (2003-05-01). «Astronomy: Elements of surprise». Nature. 423 (29): 29. Bibcode:2003Natur.423…29C. doi:10.1038/423029a. PMID 12721614. S2CID 4330398.

- ^ Kunde, V.; Hanel, R.; Maguire, W.; Gautier, D.; Baluteau, J. P.; Marten, A.; Chedin, A.; Husson, N.; Scott, N. (1982). «The tropospheric gas composition of Jupiter’s north equatorial belt /NH3, PH3, CH3D, GeH4, H2O/ and the Jovian D/H isotopic ratio». Astrophysical Journal. 263: 443–467. Bibcode:1982ApJ…263..443K. doi:10.1086/160516.

- ^ a b c d e Höll, R.; Kling, M.; Schroll, E. (2007). «Metallogenesis of germanium – A review». Ore Geology Reviews. 30 (3–4): 145–180. doi:10.1016/j.oregeorev.2005.07.034.

- ^ Frenzel, Max (2016). «The distribution of gallium, germanium and indium in conventional and non-conventional resources – Implications for global availability (PDF Download Available)». ResearchGate. Unpublished. doi:10.13140/rg.2.2.20956.18564. Archived from the original on 2018-10-06. Retrieved 2017-06-10.

- ^ Roberts, Andrew C.; et al. (December 2004). «Eyselite, Fe3+Ge34+O7(OH), a new mineral species from Tsumeb, Namibia». The Canadian Mineralogist. 42 (6): 1771–1776. doi:10.2113/gscanmin.42.6.1771.

- ^ «Archived copy» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-10-06. Retrieved 2018-10-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ «Archived copy» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-20. Retrieved 2018-10-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Goldschmidt, V. M. (1930). «Ueber das Vorkommen des Germaniums in Steinkohlen und Steinkohlenprodukten». Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse: 141–167. Archived from the original on 2018-03-03. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ^ a b Goldschmidt, V. M.; Peters, Cl. (1933). «Zur Geochemie des Germaniums». Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse: 141–167. Archived from the original on 2008-12-01. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ^ Bernstein, L (1985). «Germanium geochemistry and mineralogy». Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 49 (11): 2409–2422. Bibcode:1985GeCoA..49.2409B. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(85)90241-8.

- ^ Frenzel, Max; Hirsch, Tamino; Gutzmer, Jens (July 2016). «Gallium, germanium, indium and other minor and trace elements in sphalerite as a function of deposit type – A meta-analysis». Ore Geology Reviews. 76: 52–78. doi:10.1016/j.oregeorev.2015.12.017.

- ^ Frenzel, Max; Ketris, Marina P.; Gutzmer, Jens (2013-12-29). «On the geological availability of germanium». Mineralium Deposita. 49 (4): 471–486. Bibcode:2014MinDe..49..471F. doi:10.1007/s00126-013-0506-z. ISSN 0026-4598. S2CID 129902592.

- ^ Frenzel, Max; Ketris, Marina P.; Gutzmer, Jens (2014-01-19). «Erratum to: On the geological availability of germanium». Mineralium Deposita. 49 (4): 487. Bibcode:2014MinDe..49..487F. doi:10.1007/s00126-014-0509-4. ISSN 0026-4598. S2CID 140620827.

- ^ R.N. Soar (1977). USGS Minerals Information. U.S. Geological Survey Mineral Commodity Summaries. January 2003, January 2004, January 2005, January 2006, January 2007, January 2010. ISBN 978-0-85934-039-7. OCLC 16437701. Archived from the original on 2013-05-07. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ a b c Naumov, A. V. (2007). «World market of germanium and its prospects». Russian Journal of Non-Ferrous Metals. 48 (4): 265–272. doi:10.3103/S1067821207040049. S2CID 137187498.

- ^ a b Moskalyk, R. R. (2004). «Review of germanium processing worldwide». Minerals Engineering. 17 (3): 393–402. doi:10.1016/j.mineng.2003.11.014.

- ^ Rieke, G. H. (2007). «Infrared Detector Arrays for Astronomy». Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 45 (1): 77–115. Bibcode:2007ARA&A..45…77R. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.44.051905.092436. S2CID 26285029.

- ^ a b c Brown, Robert D. Jr. (2000). «Germanium» (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-06-08. Retrieved 2008-09-22.

- ^ «Chapter III: Optical Fiber For Communications» (PDF). Stanford Research Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-12-05. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ «Understanding Recordable & Rewritable DVD» (PDF) (First ed.). Optical Storage Technology Association (OSTA). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-04-19. Retrieved 2008-09-22.

- ^ Lettington, Alan H. (1998). «Applications of diamond-like carbon thin films». Carbon. 36 (5–6): 555–560. doi:10.1016/S0008-6223(98)00062-1.

- ^ Gardos, Michael N.; Bonnie L. Soriano; Steven H. Propst (1990). Feldman, Albert; Holly, Sandor (eds.). «Study on correlating rain erosion resistance with sliding abrasion resistance of DLC on germanium». Proc. SPIE. SPIE Proceedings. 1325 (Mechanical Properties): 99. Bibcode:1990SPIE.1325…99G. doi:10.1117/12.22449. S2CID 137425193.

- ^ Washio, K. (2003). «SiGe HBT and BiCMOS technologies for optical transmission and wireless communication systems». IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices. 50 (3): 656–668. Bibcode:2003ITED…50..656W. doi:10.1109/TED.2003.810484.

- ^ Bailey, Sheila G.; Raffaelle, Ryne; Emery, Keith (2002). «Space and terrestrial photovoltaics: synergy and diversity». Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications. 10 (6): 399–406. Bibcode:2002sprt.conf..202B. doi:10.1002/pip.446. hdl:2060/20030000611. S2CID 98370426.

- ^ Crisp, D.; Pathare, A.; Ewell, R. C. (January 2004). «The performance of gallium arsenide/germanium solar cells at the Martian surface». Acta Astronautica. 54 (2): 83–101. Bibcode:2004AcAau..54…83C. doi:10.1016/S0094-5765(02)00287-4.

- ^ Wu, Heng; Ye, Peide D. (August 2016). «Fully Depleted Ge CMOS Devices and Logic Circuits on Si» (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices. 63 (8): 3028–3035. Bibcode:2016ITED…63.3028W. doi:10.1109/TED.2016.2581203. S2CID 3231511. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-04.

- ^ Szweda, Roy (2005). «Germanium phoenix». III-Vs Review. 18 (7): 55. doi:10.1016/S0961-1290(05)71310-7.

- ^ a b Thiele, Ulrich K. (2001). «The Current Status of Catalysis and Catalyst Development for the Industrial Process of Poly(ethylene terephthalate) Polycondensation». International Journal of Polymeric Materials. 50 (3): 387–394. doi:10.1080/00914030108035115. S2CID 98758568.

- ^ Fang, Li; Kulkarni, Sameer; Alhooshani, Khalid; Malik, Abdul (2007). «Germania-Based, Sol-Gel Hybrid Organic-Inorganic Coatings for Capillary Microextraction and Gas Chromatography». Anal. Chem. 79 (24): 9441–9451. doi:10.1021/ac071056f. PMID 17994707.

- ^ Keyser, Ronald; Twomey, Timothy; Upp, Daniel. «Performance of Light-Weight, Battery-Operated, High Purity Germanium Detectors for Field Use» (PDF). Oak Ridge Technical Enterprise Corporation (ORTEC). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 26, 2007. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- ^ Ahmed, F. U.; Yunus, S. M.; Kamal, I.; Begum, S.; Khan, Aysha A.; Ahsan, M. H.; Ahmad, A. A. Z. (1996). «Optimization of Germanium for Neutron Diffractometers». International Journal of Modern Physics E. 5 (1): 131–151. Bibcode:1996IJMPE…5..131A. doi:10.1142/S0218301396000062.

- ^ Diehl, R.; Prantzos, N.; Vonballmoos, P. (2006). «Astrophysical constraints from gamma-ray spectroscopy». Nuclear Physics A. 777 (2006): 70–97. arXiv:astro-ph/0502324. Bibcode:2006NuPhA.777…70D. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.256.9318. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2005.02.155. S2CID 2360391.

- ^ Eugene P. Bertin (1970). Principles and practice of X-ray spectrometric analysis, Chapter 5.4 – Analyzer crystals, Table 5.1, p. 123; Plenum Press

- ^ Shen, C.; Trypiniotis, T.; Lee, K. Y.; Holmes, S. N.; Mansell, R.; Husain, M.; Shah, V.; Li, X. V.; Kurebayashi, H. (2010-10-18). «Spin transport in germanium at room temperature» (PDF). Applied Physics Letters. 97 (16): 162104. Bibcode:2010ApPhL..97p2104S. doi:10.1063/1.3505337. ISSN 0003-6951. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-09-22. Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- ^ Sigillito, A. J.; Jock, R. M.; Tyryshkin, A. M.; Beeman, J. W.; Haller, E. E.; Itoh, K. M.; Lyon, S. A. (2015-12-07). «Electron Spin Coherence of Shallow Donors in Natural and Isotopically Enriched Germanium». Physical Review Letters. 115 (24): 247601. arXiv:1506.05767. Bibcode:2015PhRvL.115x7601S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.247601. PMID 26705654. S2CID 13299377.

- ^ a b Ades TB, ed. (2009). «Germanium». American Cancer Society Complete Guide to Complementary and Alternative Cancer Therapies (2nd ed.). American Cancer Society. pp. 360–363. ISBN 978-0944235713.

- ^ Brown, Robert D. Jr. Commodity Survey:Germanium (PDF) (Report). US Geological Surveys. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-03-04. Retrieved 2008-09-09.

- ^ Baselt, R. (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 693–694.

- ^ Gerber, G. B.; Léonard, A. (1997). «Mutagenicity, carcinogenicity and teratogenicity of germanium compounds». Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 387 (3): 141–146. doi:10.1016/S1383-5742(97)00034-3. PMID 9439710.

External links[edit]

![]()

- Germanium at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

Not to be confused with geranium.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Germanium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | (jur-MAY-nee-əm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | grayish-white | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Ge) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Germanium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 32 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 14 (carbon group) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d10 4s2 4p2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1211.40 K (938.25 °C, 1720.85 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 3106 K (2833 °C, 5131 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 5.323 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 5.60 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 36.94 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 334 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 23.222 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −4 −3, −2, −1, 0,[2] +1, +2, +3, +4 (an amphoteric oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.01 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 122 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 122 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 211 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of germanium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centered diamond-cubic

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 5400 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 6.0 µm/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 60.2 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 1 Ω⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Band gap | 0.67 eV (at 300 K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | −76.84×10−6 cm3/mol[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 103 GPa[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 41 GPa[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 75 GPa[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.26[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 6.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-56-4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after Germany, homeland of the discoverer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prediction | Dmitri Mendeleev (1869) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Clemens Winkler (1886) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main isotopes of germanium

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Germanium is a chemical element with the symbol Ge and atomic number 32. It is lustrous, hard-brittle, grayish-white and similar in appearance to silicon. It is a metalloid in the carbon group that is chemically similar to its group neighbors silicon and tin. Like silicon, germanium naturally reacts and forms complexes with oxygen in nature.

Because it seldom appears in high concentration, germanium was discovered comparatively late in the discovery of the elements. Germanium ranks near fiftieth in relative abundance of the elements in the Earth’s crust. In 1869, Dmitri Mendeleev predicted its existence and some of its properties from its position on his periodic table, and called the element ekasilicon. In 1886, Clemens Winkler at Freiberg University found the new element, along with silver and sulfur, in the mineral argyrodite. Winkler named the element after his country, Germany. Germanium is mined primarily from sphalerite (the primary ore of zinc), though germanium is also recovered commercially from silver, lead, and copper ores.

Elemental germanium is used as a semiconductor in transistors and various other electronic devices. Historically, the first decade of semiconductor electronics was based entirely on germanium. Presently, the major end uses are fibre-optic systems, infrared optics, solar cell applications, and light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Germanium compounds are also used for polymerization catalysts and have most recently found use in the production of nanowires. This element forms a large number of organogermanium compounds, such as tetraethylgermanium, useful in organometallic chemistry. Germanium is considered a technology-critical element.[6]

Germanium is not thought to be an essential element for any living organism. Similar to silicon and aluminium, naturally-occurring germanium compounds tend to be insoluble in water and thus have little oral toxicity. However, synthetic soluble germanium salts are nephrotoxic, and synthetic chemically reactive germanium compounds with halogens and hydrogen are irritants and toxins.

History[edit]

Prediction of germanium, «?=70» (periodic table 1869)

In his report on The Periodic Law of the Chemical Elements in 1869, the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev predicted the existence of several unknown chemical elements, including one that would fill a gap in the carbon family, located between silicon and tin.[7] Because of its position in his periodic table, Mendeleev called it ekasilicon (Es), and he estimated its atomic weight to be 70 (later 72).

In mid-1885, at a mine near Freiberg, Saxony, a new mineral was discovered and named argyrodite because of its high silver content.[note 1] The chemist Clemens Winkler analyzed this new mineral, which proved to be a combination of silver, sulfur, and a new element. Winkler was able to isolate the new element in 1886 and found it similar to antimony. He initially considered the new element to be eka-antimony, but was soon convinced that it was instead eka-silicon.[9][10] Before Winkler published his results on the new element, he decided that he would name his element neptunium, since the recent discovery of planet Neptune in 1846 had similarly been preceded by mathematical predictions of its existence.[note 2] However, the name «neptunium» had already been given to another proposed chemical element (though not the element that today bears the name neptunium, which was discovered in 1940).[note 3] So instead, Winkler named the new element germanium (from the Latin word, Germania, for Germany) in honor of his homeland.[10] Argyrodite proved empirically to be Ag8GeS6.

Because this new element showed some similarities with the elements arsenic and antimony, its proper place in the periodic table was under consideration, but its similarities with Dmitri Mendeleev’s predicted element «ekasilicon» confirmed that place on the periodic table.[10][17] With further material from 500 kg of ore from the mines in Saxony, Winkler confirmed the chemical properties of the new element in 1887.[9][10][18] He also determined an atomic weight of 72.32 by analyzing pure germanium tetrachloride (GeCl

4), while Lecoq de Boisbaudran deduced 72.3 by a comparison of the lines in the spark spectrum of the element.[19]

Winkler was able to prepare several new compounds of germanium, including fluorides, chlorides, sulfides, dioxide, and tetraethylgermane (Ge(C2H5)4), the first organogermane.[9] The physical data from those compounds—which corresponded well with Mendeleev’s predictions—made the discovery an important confirmation of Mendeleev’s idea of element periodicity. Here is a comparison between the prediction and Winkler’s data:[9]

| Property | Ekasilicon Mendeleev prediction (1871) | Germanium Winkler discovery (1887) |

|---|---|---|

| atomic mass | 72.64 | 72.63 |

| density (g/cm3) | 5.5 | 5.35 |

| melting point (°C) | high | 947 |

| color | gray | gray |

| oxide type | refractory dioxide | refractory dioxide |

| oxide density (g/cm3) | 4.7 | 4.7 |

| oxide activity | feebly basic | feebly basic |

| chloride boiling point (°C) | under 100 | 86 (GeCl4) |

| chloride density (g/cm3) | 1.9 | 1.9 |

Until the late 1930s, germanium was thought to be a poorly conducting metal.[20] Germanium did not become economically significant until after 1945 when its properties as an electronic semiconductor were recognized. During World War II, small amounts of germanium were used in some special electronic devices, mostly diodes.[21][22] The first major use was the point-contact Schottky diodes for radar pulse detection during the War.[20] The first silicon-germanium alloys were obtained in 1955.[23] Before 1945, only a few hundred kilograms of germanium were produced in smelters each year, but by the end of the 1950s, the annual worldwide production had reached 40 metric tons (44 short tons).[24]

The development of the germanium transistor in 1948[25] opened the door to countless applications of solid state electronics.[26] From 1950 through the early 1970s, this area provided an increasing market for germanium, but then high-purity silicon began replacing germanium in transistors, diodes, and rectifiers.[27] For example, the company that became Fairchild Semiconductor was founded in 1957 with the express purpose of producing silicon transistors. Silicon has superior electrical properties, but it requires much greater purity that could not be commercially achieved in the early years of semiconductor electronics.[28]

Meanwhile, the demand for germanium for fiber optic communication networks, infrared night vision systems, and polymerization catalysts increased dramatically.[24] These end uses represented 85% of worldwide germanium consumption in 2000.[27] The US government even designated germanium as a strategic and critical material, calling for a 146 ton (132 tonne) supply in the national defense stockpile in 1987.[24]

Germanium differs from silicon in that the supply is limited by the availability of exploitable sources, while the supply of silicon is limited only by production capacity since silicon comes from ordinary sand and quartz. While silicon could be bought in 1998 for less than $10 per kg,[24] the price of germanium was almost $800 per kg.[24]

Characteristics[edit]

Under standard conditions, germanium is a brittle, silvery-white, semi-metallic element.[29] This form constitutes an allotrope known as α-germanium, which has a metallic luster and a diamond cubic crystal structure, the same as diamond.[27] While in crystal form, germanium has a displacement threshold energy of

Germanium is a semiconductor having an indirect bandgap, as is crystalline silicon. Zone refining techniques have led to the production of crystalline germanium for semiconductors that has an impurity of only one part in 1010,[32]

making it one of the purest materials ever obtained.[33]

The first metallic material discovered (in 2005) to become a superconductor in the presence of an extremely strong electromagnetic field was an alloy of germanium, uranium, and rhodium.[34]

Pure germanium is known to spontaneously extrude very long screw dislocations, referred to as germanium whiskers. The growth of these whiskers is one of the primary reasons for the failure of older diodes and transistors made from germanium, as, depending on what they eventually touch, they may lead to an electrical short.[35]

Chemistry[edit]

Elemental germanium starts to oxidize slowly in air at around 250 °C, forming GeO2 .[36] Germanium is insoluble in dilute acids and alkalis but dissolves slowly in hot concentrated sulfuric and nitric acids and reacts violently with molten alkalis to produce germanates ([GeO

3]2−

). Germanium occurs mostly in the oxidation state +4 although many +2 compounds are known.[37] Other oxidation states are rare: +3 is found in compounds such as Ge2Cl6, and +3 and +1 are found on the surface of oxides,[38] or negative oxidation states in germanides, such as −4 in Mg

2Ge. Germanium cluster anions (Zintl ions) such as Ge42−, Ge94−, Ge92−, [(Ge9)2]6− have been prepared by the extraction from alloys containing alkali metals and germanium in liquid ammonia in the presence of ethylenediamine or a cryptand.[37][39] The oxidation states of the element in these ions are not integers—similar to the ozonides O3−.

Two oxides of germanium are known: germanium dioxide (GeO

2, germania) and germanium monoxide, (GeO).[31] The dioxide, GeO2 can be obtained by roasting germanium disulfide (GeS

2), and is a white powder that is only slightly soluble in water but reacts with alkalis to form germanates.[31] The monoxide, germanous oxide, can be obtained by the high temperature reaction of GeO2 with Ge metal.[31] The dioxide (and the related oxides and germanates) exhibits the unusual property of having a high refractive index for visible light, but transparency to infrared light.[40][41] Bismuth germanate, Bi4Ge3O12, (BGO) is used as a scintillator.[42]

Binary compounds with other chalcogens are also known, such as the disulfide (GeS

2), diselenide (GeSe

2), and the monosulfide (GeS), selenide (GeSe), and telluride (GeTe).[37] GeS2 forms as a white precipitate when hydrogen sulfide is passed through strongly acid solutions containing Ge(IV).[37] The disulfide is appreciably soluble in water and in solutions of caustic alkalis or alkaline sulfides. Nevertheless, it is not soluble in acidic water, which allowed Winkler to discover the element.[43] By heating the disulfide in a current of hydrogen, the monosulfide (GeS) is formed, which sublimes in thin plates of a dark color and metallic luster, and is soluble in solutions of the caustic alkalis.[31] Upon melting with alkaline carbonates and sulfur, germanium compounds form salts known as thiogermanates.[44]

Four tetrahalides are known. Under normal conditions GeI4 is a solid, GeF4 a gas and the others volatile liquids. For example, germanium tetrachloride, GeCl4, is obtained as a colorless fuming liquid boiling at 83.1 °C by heating the metal with chlorine.[31] All the tetrahalides are readily hydrolyzed to hydrated germanium dioxide.[31] GeCl4 is used in the production of organogermanium compounds.[37] All four dihalides are known and in contrast to the tetrahalides are polymeric solids.[37] Additionally Ge2Cl6 and some higher compounds of formula GenCl2n+2 are known.[31] The unusual compound Ge6Cl16 has been prepared that contains the Ge5Cl12 unit with a neopentane structure.[45]

Germane (GeH4) is a compound similar in structure to methane. Polygermanes—compounds that are similar to alkanes—with formula GenH2n+2 containing up to five germanium atoms are known.[37] The germanes are less volatile and less reactive than their corresponding silicon analogues.[37] GeH4 reacts with alkali metals in liquid ammonia to form white crystalline MGeH3 which contain the GeH3− anion.[37] The germanium hydrohalides with one, two and three halogen atoms are colorless reactive liquids.[37]

The first organogermanium compound was synthesized by Winkler in 1887; the reaction of germanium tetrachloride with diethylzinc yielded tetraethylgermane (Ge(C

2H

5)

4).[9] Organogermanes of the type R4Ge (where R is an alkyl) such as tetramethylgermane (Ge(CH

3)

4) and tetraethylgermane are accessed through the cheapest available germanium precursor germanium tetrachloride and alkyl nucleophiles. Organic germanium hydrides such as isobutylgermane ((CH

3)

2CHCH

2GeH

3) were found to be less hazardous and may be used as a liquid substitute for toxic germane gas in semiconductor applications. Many germanium reactive intermediates are known: germyl free radicals, germylenes (similar to carbenes), and germynes (similar to carbynes).[46][47] The organogermanium compound 2-carboxyethylgermasesquioxane was first reported in the 1970s, and for a while was used as a dietary supplement and thought to possibly have anti-tumor qualities.[48]